In my early Caribbean childhood of the 1960s and 1970s after leaving England, the country of my birth, stories surrounded us. Often, they were whispered and overheard in partial, redacted fragments, or they were spit out into the air with force, the words ricocheting off the walls and buildings of our individual and collective histories and rebounding in fragments to listeners in myriad shapes and patterns. At other times, the stories were gently ladled—soft, soothing, and nourishing in the recollections of elder women and men who chose their words with care, deboning the sharp bits while maintaining the flesh of the experience for young listeners.

As children, my brother and I were often reminded never to eat fried fish while simultaneously carrying on a vigorous conversation because the slipperiness and sharpness of the fish bones made them more likely to shift from between our teeth and lodge sharply somewhere between the first bite and the swallowing of piquant deliciousness. Fairytale horror always got our attention. I regard the silence of eating fried fish as one of the crucial lessons of conversation because it taught us how to listen carefully. Now while fish bones were discarded, the bones of chicken and other meat were often ground to a powdery mass—“down to the marrow”—the chewing of which was an enjoyment of the meal. In this way, eating bones were both cautionary as well as savoured metaphors about speech, listening, and enjoyment.

We grew up with grandparents, people born at the turn of the last century, descendants of the enslaved, on small islands of the Eastern Caribbean in what was then a far-flung shore of Britain’s imperial project. At one time in the late eighteenth century, Admiral Horatio Nelson and his soldiers were stationed there in Antigua, at the naval dockyard built by enslaved folks on the south coast looking over the waves at Guadaloupe. Sitting on the front stone steps of our grandparents’ home, too young for school, we too were sentinels who drank in salt air. There were a few cars and trucks, but mostly we watched people; they embodied the world beyond garden gates, doors, and louvres (windows). We saw children in their freshly pressed uniforms going to and from school and grown folk walking by and calling out their greetings, selling their wares with snatches of song, including fish, ice wrapped in burlap, and salt peanuts. And if there were praises and curses belonging to dramas that began long before they walked by, we heard those, too.

We grew up with grandparents, people born at the turn of the last century, descendants of the enslaved, on small islands of the Eastern Caribbean in what was then a far-flung shore of Britain’s imperial project. At one time in the late eighteenth century, Admiral Horatio Nelson and his soldiers were stationed there in Antigua, at the naval dockyard built by enslaved folks on the south coast looking over the waves at Guadaloupe. Sitting on the front stone steps of our grandparents’ home, too young for school, we too were sentinels who drank in salt air. There were a few cars and trucks, but mostly we watched people; they embodied the world beyond garden gates, doors, and louvres (windows). We saw children in their freshly pressed uniforms going to and from school and grown folk walking by and calling out their greetings, selling their wares with snatches of song, including fish, ice wrapped in burlap, and salt peanuts. And if there were praises and curses belonging to dramas that began long before they walked by, we heard those, too.

My brother and I traveled through the centuries, daily. We walked by structures, including the Anglican cathedral that we visited each Sunday, built and rebuilt over the last few centuries. Nothing was designated a historical site. I do not recall any plaques or markers. There were gravestones and cannons and cannon balls, material evidence from a colonial past. A woman selling fruit around the corner from our house greeted my grandfather in his mother tongue, Antillean French Creole, every day as he took his constitutional walk after lunch. I imagine her saying “Sa kap fet?” (How’s it going?). The scales on which she and other market women confirmed the price of her goods, accurately pre-weighed by her touch, were heavy dark metal forged before our time. When we returned to the house with longer shadows in tow perhaps my uncle would be there, his car parked outside and the gentle tick tock of his wristwatch marking modern time. We learned to move between these various eras. We were travelers seated on the front steps of the house, books and words and stories for fuel, hurtling through the atmosphere from which we took deep garden-perfumed gulps, sunglasses a barrier protecting our eyes from some alternate sun.

After flying to Canada in the early 1970s in a giant version of the red plastic plane from the cereal box, we felt the shift and change, jarringly, in the unaccustomed motion of escalators and elevators and trains and buses and another English language. But the stories, we remembered the stories, and we learned to chew and spit and talk and write them. In my teaching and design of Caribbean and African Diaspora religious and cultural studies courses, these storying practices contribute to imaginative pedagogies. They are especially useful when engaging students in the study of topics which are potentially difficult and traumatic. Storying as a teaching method has the capacity to both disrupt and challenge as well as to protect. Storying invites multiple vantage points and critical assessment. Finding the story bones is a process of meaningful engagement with the past and holds the potential to connect our various worlds of being as teachers, scholars, and learners.

|

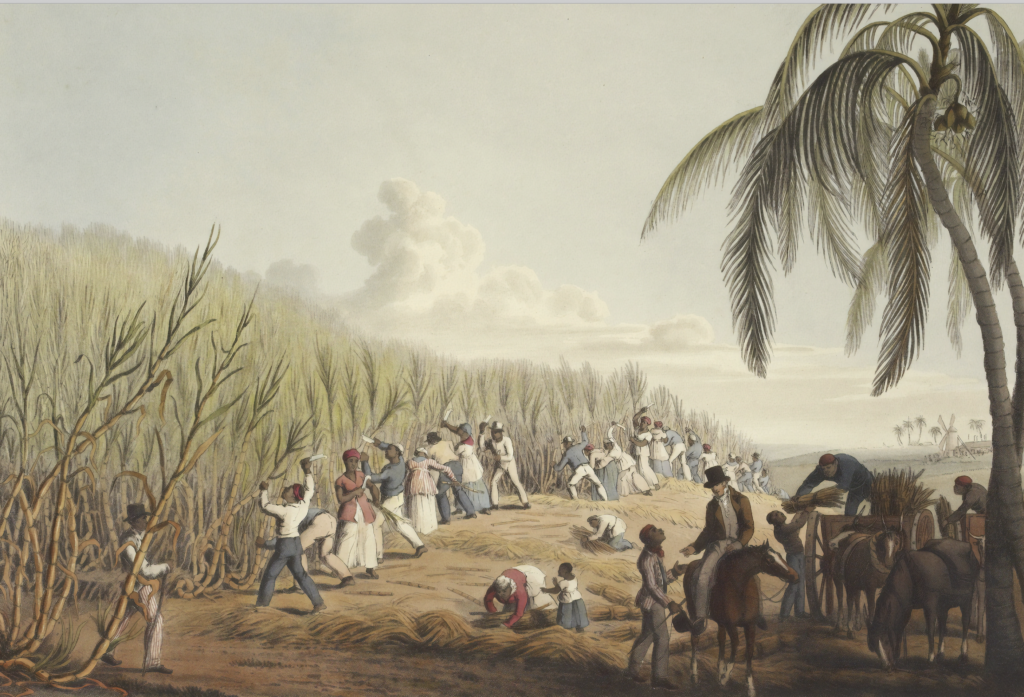

Enslaved people cutting the sugar cane on the Island of Antigua, 1823. Download this photo by British Library on Unsplash

unsplash.com

|

I enjoyed the flavor in which the story was conveyed. Well done.