The final report of Canada’s Truth and Reconciliation Commission led by Justice Murray Sinclair, on the tragic impacts of Indian Residential Schools, was released in 2015. It included 94 Calls to Action, with several of these Calls relating directly to higher education. For instance, Call to Action number 62 urges postsecondary institutions to educate teachers on how to integrate Indigenous knowledge and teaching methods into classrooms. One way to begin addressing integration has to do with unsettling settler colonial worldviews, histories, and perspectives. How might this unsettling be done in a good way?

Mi’kmaw Elder Albert Marshall states that Two-Eyed Seeing is “To see from one eye with the strengths of Indigenous ways of knowing, and to see from the other eye with the strengths of Western ways of knowing, and to use both of these eyes together” ( 2012, 335). In using both eyes, my students and I need to locate ourselves in own stories of identification in the classroom. I would like to be aware, and I want my students to be especially aware, of the issues and history of self-identification. According to Anuik, “Self-identification has an impact on teachers’ practices, and understanding how people identify can help teachers to adapt learning environments to meet their needs” (2019, 107). One way to get at this is through stories of identification—my own and my students.’ I ask my students to identify two labels that others at school had used to describe them in the past. I then share my two identifiers and tell my story about teacher judgement and a school system’s misjudgment of an assessment.

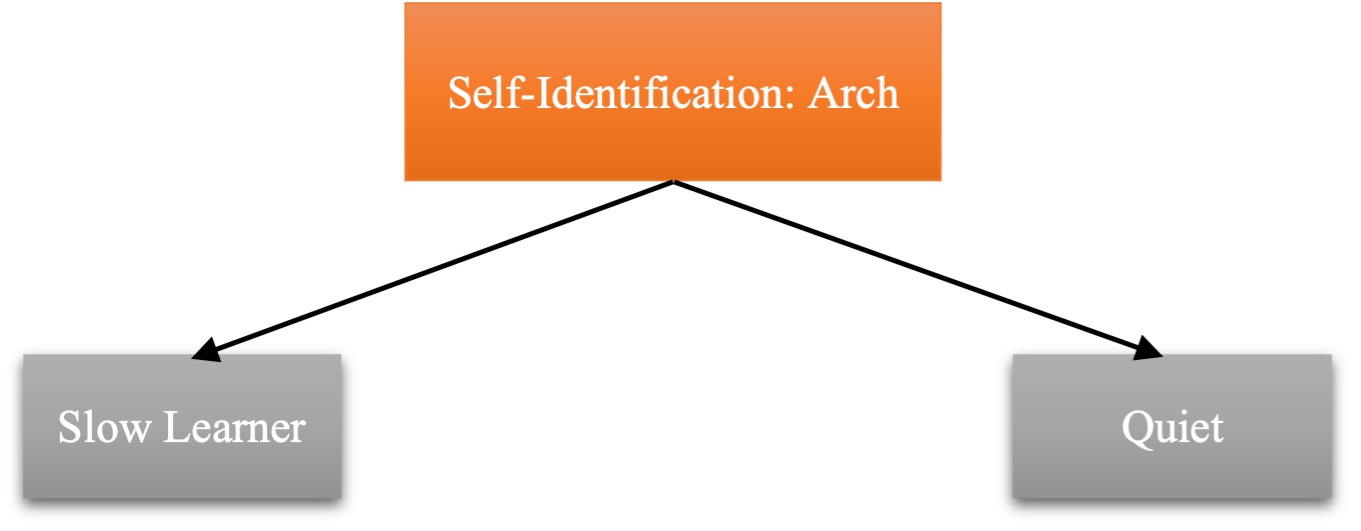

If one aspect of an indigenous way of knowing is about relationality and building relationships of trust with my students, it requires me to be vulnerable with my story. So, when I was in third grade, I brought home a report card that ranked me “below average” in relation to my peers. A row of failing grades ran down the report card beside each topic. The report card generated a meeting between my parents, the teacher, and the principal and a series of assessments. The meeting with my parents was awkward because my parents didn’t speak or understand English very well, and the principal wanted to meet after school and my parents, who worked at a Chinese restaurant, had to take time off to visit the school. The test results indicated that I was a slow learner (I didn’t understand and speak English very well) and may have a cognitive impairment. I knew this verdict made me different from my peers. I thought that every kid at school knew about my issue, and I felt shame. My parents felt shame as well because they came to Canada to make a better life for their children. I mixed up the assessment results with being stupid—what else was I to think since my report card showed that! I chose to disengage. If I stayed quiet, then no one would suspect I had an intelligence issue; I didn’t participate in class even if I knew the answers better than my peers. My style carried me through to grade 8, when my enthusiastic gym teacher said I was very quiet and needed to speak out more in class. That early assessment and teacher’s judgements failed me. As a child, I feared that if my teachers said I had a cognitive issue, then they would treat me differently than my peers—if only they knew where I am today!

I then ask my students to look at their identifiers and ask if they accurately represent who they thought they were? In most cases, they were an inaccurate representation of who they thought they were. I show them this diagram:

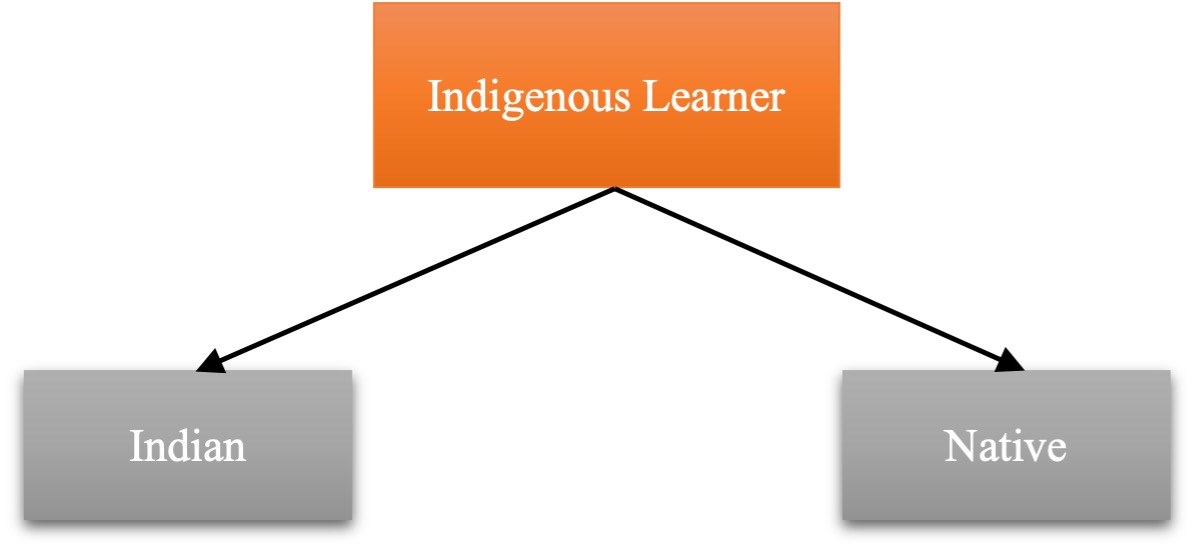

Discussing this diagram allows my students to begin to understand that indigenous students have identities conditioned by Canadian legislation which was historically rooted. Naming students “Indian” or “Aboriginal” had a negative impact because being labelled one or the other triggered fear that an educator would throw the student into a box that held a collection of negative stereotypes or misinterpretations of a person that needed to be fixed.

How might I move this further with self-identification? Going back to Mi’kmaw Elder Albert Marshall’s concept of Two-Eyed Seeing has been a helpful way to reflect on my own teaching practices and course design, and the ways that they might impact my students’ own identity and spiritual formation as they move out into the wider world after graduation. For myself, I wonder at times if I simultaneously need a third eye to think and voice more creatively an Asian way of knowing as well?

References

Anuik, J. 2019. “If You Say I am Indian, What Will You Do? History and Self-Identification at Humanity’s Intersection.” In Knowing the Past, Facing the Future: Indigenous Education in Canada, edited by S. Carr-Stewart, 106-117. Vancouver, BC: Purich Books.

Bartlett, C., Marshall, M., and Marshall, A. 2012. “Two-Eyed Seeing and Other Lessons Learned Within a Co-Learning Journey of Bringing Together Indigenous and Mainstream Knowledges and Ways of Knowing.” Journal of Environmental Studies and Sciences 2(4): 331-340. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13412-012-0086-8.