If there is one thing I’ve learned from my 20 students in a new course, “Religion and Racism in America” this semester it’s this: how we go about engaging racism in the classroom may be just as important, if not more, than what sources we use to do so.

- Racism is not an intellectual reality, but an experiential one. Critical race theorist George Yancy is right (not that I ever doubted him!). Racism is an embodied experience and not simply a sociological phenomenon, no matter how intellectually demanding or interdisciplinary the study of it might be. See Yancy’s New York Times op-ed on Trayvon Martin (September 1, 2013). I continue to forget that insight, not only because of my whiteness but also given my proclivity for retreating to my intellectual comfort zone when it comes to racism. Reminding myself that racism is primarily experiential keeps me rooted in the wisdom present in the many experiences we hold in our bodies in each class session: our family histories, our encounters with racism on campus, or our collisions with the color line off campus, and our reactions to the seemingly never ending supply of racialized media coverage of just about everything. Rather than being fearful of those experiences, my students and I have tried to shed light on them, situate them in larger social contexts, and point to their implications for regarding self and other. As a result course content has often taken a backseat to learning how to simply be with each other in the midst of that messy human brokenness, and to keep talking with each other and relating to each other for 75 minutes twice a week (at 8 AM no less!). While this way of being together hasn’t been the norm, a few things have seemed to helped us stay grounded in experience as we wade through all of the content:

- Journaling. In the second week I asked students to reflect on a moment when they were aware of their racial identity and to identify feelings associated with that experience. Their answers have given me the imperative – and tragically ample material – to keep us rooted in the personal. I’ve encouraged critical reflection in subsequent entries, pushing students to do some of that situating work on their own so that they might get better at doing so with others.

- Historical and personal timeline. We charted the chronological construction of the “white racial frame” in the U.S. (using Joe Feagin’s 2013 book of the same title) from 1500 to 2014 on a sheet of butcher paper that ran the entire length of the classroom. Students worked in groups to identify key historical dates, and then marked their families’ entrances into the timeline, providing a chance to reflect on ways in which the white racial frame shapes their current experience of their bodies and culture, as well as other bodies and cultures.

- You cannot teach anti-racism, you can only facilitate the process of becoming anti-racist. Teaching a course on racism unearths a host of problems with the “sage on the stage” approach, many of which have been referenced in other insightful posts on this blog. In Two-Faced Racism (2007) Feagin implicitly underscores the problem with this pedagogical approach when it comes to the ways that racism is performed on public front stages and private back stages of everyday life. Our classrooms have both front and back stages, making them precarious places for sages attempting to tell students something about racism. Facilitators, on the other hand, transform front and back stages into spaces where the learning process can unfold by creating conditions—physical, emotional, mental, and chronological—for self-awareness, empathy, and agency. They manage, massage, encourage, move things to back burners or turn up the heat, let things come off the rails and put things back on track. Facilitators are in control but are not controlling. Here are a few things that have worked so far for me in terms of striking that balance:

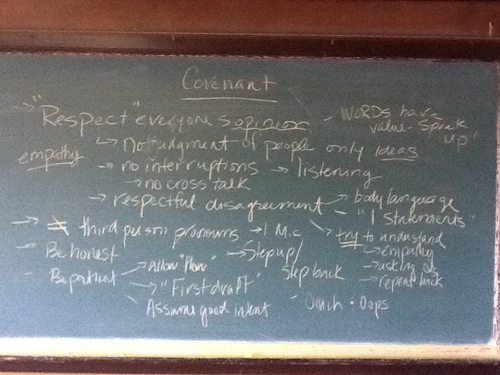

- We established a classroom covenant where students named what they need from each other and from me in order to engage what Cornel West calls “fearless speech” about racism. One month into the course, we evaluated our progress on achieving that covenant through an anonymous survey that asked for honest feedback. I shared the feedback with everyone, and then asked for suggestions on how we all could do better in particular areas. We’ve all tried to step up.

- Students repeatedly indicated on that survey that they “don’t really know each other,” making fearless speech difficult. So I’ve tried to provide regular opportunities for them to get to know each other in and outside of the classroom. Icebreakers (Love, Race and Liberation: ‘Til the White Day Is Done (2005) has been helpful), one to one meetings with peers outside of class, small group work, and games like Jeopardy (made it myself via jeopardy labs!) and Monopoly (see Jost, Whitfield and Jost’s article in Multicultural Education, Fall 2005) have provided chances to move beyond artificial racial boundaries that render them strangers to each other.

My syllabus was set before Michael Brown’s death caught the attention of the nation, but the many prophetic things I’ve read and learned since, particularly from my students, only reinforce my sense that the end goal of my course isn’t teaching about racism, but rather facilitating its undoing one class session at a time. To that end, I will be a perpetual student. Thank goodness there are still a few weeks left.