In Interfaith Justice and Peacemaking, an integrative core class which explores the history of tolerance, intolerance, and interfaith efforts in the United States, one of the core texts we use is Eboo Patel’s Out of Many Faiths: Religious Diversity and the American Experience (2018). Central to Patel’s argument is that America needs new, more inclusive civil religious narratives. His book chronicles some of the ways in which Americans have expanded civil religious narratives in the past, however imperfectly, through the invention of the phrase “our Judeo-Christian heritage” in the mid-twentieth century as well as through expanding notions of whiteness. According to Patel, we are at a pivotal juncture in our nation’s history. We need new narratives. Without them, whole swaths of people will continue to feel unwelcome and alienated, and since the health of our civil society depends on civic participation from all of its citizens, our failure to create new, more inclusive stories of who we are could have disastrous consequences.

In Interfaith Justice and Peacemaking, an integrative core class which explores the history of tolerance, intolerance, and interfaith efforts in the United States, one of the core texts we use is Eboo Patel’s Out of Many Faiths: Religious Diversity and the American Experience (2018). Central to Patel’s argument is that America needs new, more inclusive civil religious narratives. His book chronicles some of the ways in which Americans have expanded civil religious narratives in the past, however imperfectly, through the invention of the phrase “our Judeo-Christian heritage” in the mid-twentieth century as well as through expanding notions of whiteness. According to Patel, we are at a pivotal juncture in our nation’s history. We need new narratives. Without them, whole swaths of people will continue to feel unwelcome and alienated, and since the health of our civil society depends on civic participation from all of its citizens, our failure to create new, more inclusive stories of who we are could have disastrous consequences.

In Out of Many Faiths, Patel focuses on the Muslim-American experience in particular, highlighting ways in which Muslims have been excluded from American society, not unlike what Jews and Catholics experienced at other moments in our history. He also highlights ways in which Muslims are working to expand our civil religious narrative. The somewhat off-color and yet unexpectedly unifying SNL monologue delivered by Aziz Ansari the night after Donald J. Trump was elected president is, according to Patel, one such example. Towards the end of the semester this year, I invited students to highlight other recent examples in the media of artists and performers and making efforts to expand our civil religious narrative.

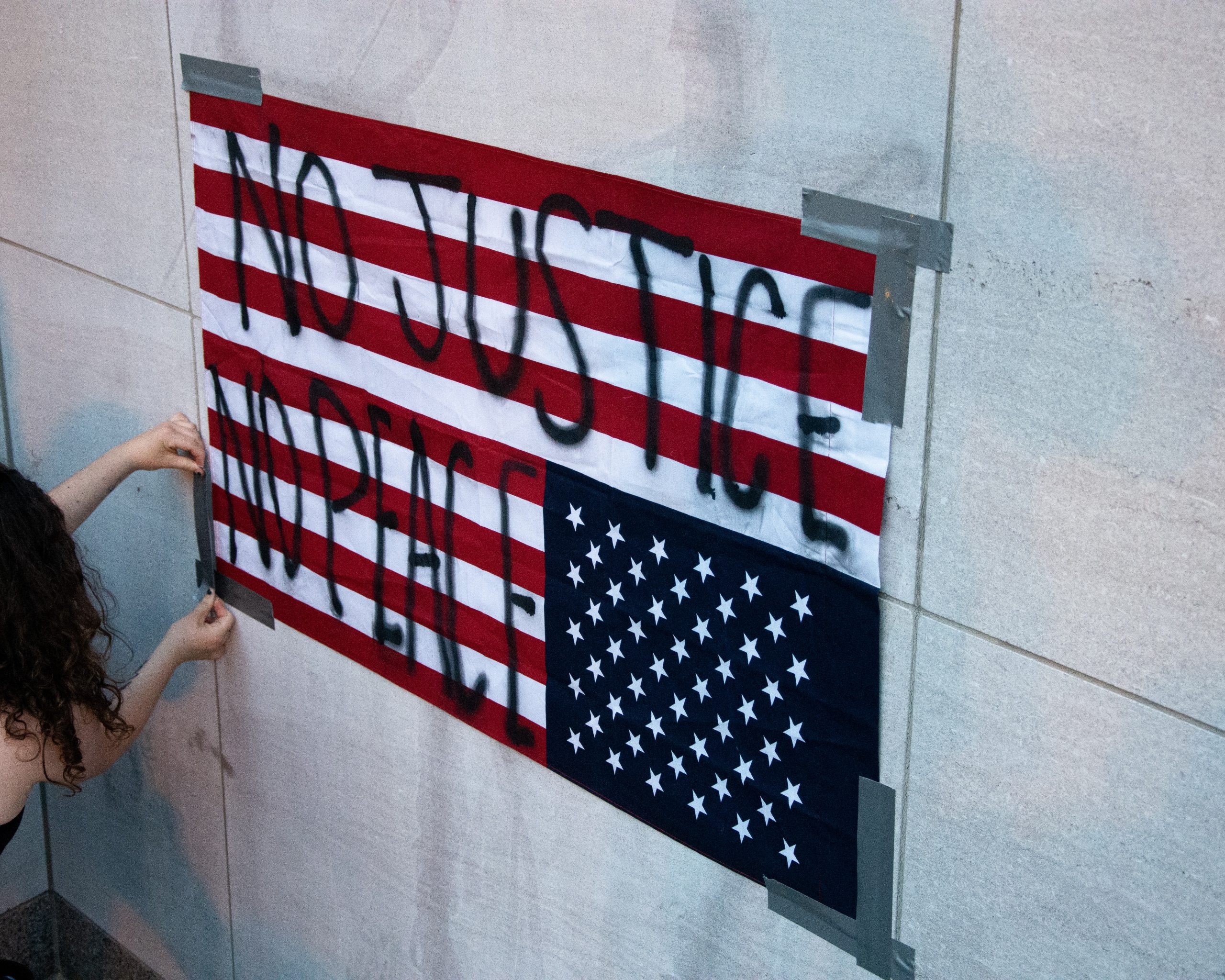

One student presented on Jennifer Lopez’s performance of “This Land is Your Land” at the Biden/Harris inauguration. He argued that Lopez’s performance of this important American folk anthem expands the civil religious narrative by linking a population of people who sometimes feel unwelcome—Hispanics—with a powerful and pervasive American symbol, suggesting that they are. Another student presented on the Black Eyed Peas’ 2009 release of the song “Where is the Love?” featuring black and brown Americans against the backdrop of one of the most prominent of civil religious symbols, the American flag, to the tune of the powerful lyrics calling for unity and love.

Just days after these presentations, I attended our university’s commencement in which a Jewish student was asked to deliver the invocation. Given that my university is Jesuit Catholic, this felt like an important moment. I was moved to tears by the eloquence with which she invoked a spirit of blessing upon our community. I’m not sure asking this student to deliver the invocation was an expansion of our civil religious narrative, given that Americans are already generally comfortable with prayers from Christian and Jewish traditions. It did, however, feel like a possible expansion of what it means for us to be Jesuit. Perhaps inviting students of various faiths to lead us in prayer is not a watering down of our Jesuit identity, but rather a truer expression of who we are. Or was it merely token, even exploitative? Did asking her to represent herself in this way cover up all the ways in which we have failed and continue to fail to build a more inclusive community?

As part of a faculty reading group on Khyati Joshi’s new book White Christian Privilege (2020), several of us have been discussing the question, how is Regis Catholic? On a micro level, it’s the same question I have been asking my students to think about all semester, how are we American? In other words, what values hold us together? And can those same sets of values be used as a source of inspiration to build a more inclusive and religiously diverse community?

My students in Interfaith Justice and Peacemaking struggled to answer this question. When discussing the narratives we tell about who we are as a nation, some identified with Nikki Haley’s speech at the 2020 Republican convention, where she argues that “America is not a racist nation,” or, as she describes, at least not fundamentally so. Other students found Zenobia Warfield’s (2021) story of America, “This is America,” more compelling. In it, Warfield argues that the white supremacist insurrection on the capital wasn’t un-American as many claimed; it was in fact emblematic of who we are as a nation, as “this country was founded on violence and desecration.” This was a difficult, emotionally-laden conversation to facilitate, the kind Khyati Joshi urges educators to engage with, rather than shy away from. For we all have different levels of investment in the systems that uphold religious and racial hierarchies and dismantling these systems requires emotional introspection (209).

In the faculty reading group on Joshi’s book we reflected on our recent participation in our university’s commencement ceremony, discussing all the moments when we were asked to participate in both civil religion and the traditions of our Jesuit university. Not all of us were comfortable removing our hats, or standing for the national anthem, and though moved by the invocation performed by our Jewish student, some of us worried she had been used. We do not have consensus about what it means to be a Jesuit university, and thus how we should represent ourselves at such a ceremony. Nor is there consensus about who we are as Americans. If we want to expand our civil religious narrative, how do we go about doing so? Do we need to build consensus first? Does that begin in the classroom? Does it take place in the planning of commencement ceremonies? There is a lot of emotional investment in these questions. Fears will surface when we start to talk about changing the narrative of who we are at a national or collegiate level—fears that reshaping, or expanding, will result in something being lost.

I would argue that neither our national identities, nor our religious identities (at the personal or college level), need to be lost in order for us to become more inclusive, but identities do need to change, and there will be growing pains that come with that change. It is my hope that Joshi’s approach, of foregrounding the emotional together with the intellectual, can provide us with useful resources as we navigate these growing pains.

I would argue that neither our national identities, nor our religious identities (at the personal or college level), need to be lost in order for us to become more inclusive, but identities do need to change, and there will be growing pains that come with that change. It is my hope that Joshi’s approach, of foregrounding the emotional together with the intellectual, can provide us with useful resources as we navigate these growing pains.

Image #1 Jason Leung @ Unsplash

Image #2 Lucas Alexander @ Unsplash

Image #3 Jordan Crawford @ Unsplash

Image #4 Koshu Kunii @ Unsplash

I think classes like these are very important, congratulations on the initiative.